Slingshot Aerospace harnessing AI to track suspicious satellites

WASHINGTON — When Russia launched the Luch Olymp K-2 geostationary spy satellite in March, analysts expected it would carry out signals intelligence-gathering missions much like its predecessor Luch Olymp-K-1 that has been in orbit since 2014.

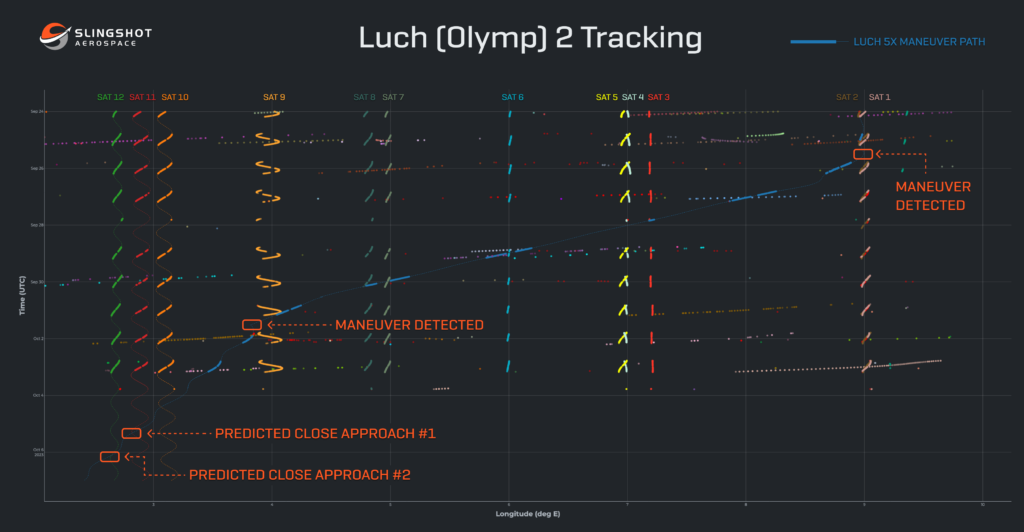

Slingshot Aerospace, a space data analytics firm focused on spaceflight safety, this week unveiled data that shows that Russia’s new spy satellite, also known as Luch-2, is conducting operations akin to those of its predecessor Luch-1, raising fresh concerns about espionage in space.

The company’s space tracking software identified multiple maneuvers by Luch-2 that are highly reminiscent of the behavior exhibited by Luch-1, which in 2015 caused an international stir when it parked itself between two Intelsat commercial communications satellites for five months.

A series of manuevers that began Sept. 26, according to Slingshot, show that Luch-2 drifted westward at a speed of about 1 degree per day before slowing down Oct. 2 to visit another “neighborhood” of GEO spacecraft.

Looking for abnormal behaviors

Slingshot’s vice president of strategy and policy Audrey Schaffer said these maneuvers were detected by the company’s automated software that tracks all satellites.

“We weren’t necessarily watching this satellite. We were just looking for things that stood out, for abnormal behaviors,” Schaffer told SpaceNews.

Slingshot did not disclose what satellites Luch-2 might have been spying on. But Schaffer said this information could be helpful for any government or commercial satellite operator concerned about security in space.

“We think that these insights are actionable, from a military and from a commercial perspective,” she said. Luch-2 does not get close enough to any satellite to set off a collision warning from the U.S. Space Force, known as a conjunction alert. “But just because it’s not close enough to be a safety threat doesn’t mean it doesn’t potentially present a security threat,” Schaffer said.

“If you are a commercial communication satellite company you may not want a Russian spy satellite listening in on your communications,” she added.

According to Michael Clonts, director of space domain awareness initiatives at Kratos Defense, Luch-2 carried similar payloads to the earlier model. However, “with a decade of additional technology development available to Luch-2, it likely packs more advanced signals intelligence capabilities and operational techniques.”

Slingshot describes its space tracking software as a “machine learning-based object profiling engine” that pulls data from multiple sources.

The system tracked Luch-2’s westward drift and predicted where it was headed, said Schaffer.

Capabilities to predict a satellite’s trajectory are not easy to achieve, she said. “The difficult aspect of maneuver detection is that when you look backwards, historically it can be obvious that a satellite maneuvered.” In real time, however, “it’s difficult to tell if a satellite is maneuvering on purpose or if it has been misplaced by data tracking systems.”

Slingshot’s algorithm was able to detect Luch-2’s maneuvers as soon as they were available in the data without having to look back at long-term patterns, she said.

The algorithm is trained to decide what is normal or abnormal for a particular orbit and sends a notification when something is unusual and needs to be looked at. “So we went back and tasked our sensors to essentially validate that what we were seeing from our algorithms was correct,” Schaffer added.

Inspector satellites like Luch-1 and Luch-2 are expected to drift by, take pictures, and continue on their way. A signals intelligence spy satellite will loiter for long periods of time near its target satellite or group of satellites. “That’s what we saw historically with the original Luch-1 satellite,” Schaffer said.

Luch-2 stayed in the same area from May until late September, when it started to drift, she said. “The takeaway is that its pattern of life is very similar to the pattern of life of the original Luch.”

Schaffer, a former White House space policy official, said these types of satellite manuevers raise suspicion. “There are a number of international conversations going on right now about what are the right norms of responsible behavior in outer space,” she said. “And activities like this should absolutely be considered when the international community develops those rules of the road that apply to space operators.”

It’s also notable, she said, that private companies are providing insights and space domain awareness that previously were only accessible from military systems. “But that’s really not true anymore,” Schaffer said. “You have companies that are generating their own space domain awareness data with their own telescope networks.”