Anna Biller on How the Gothic Gives Voice to Women’s Pleasure—and Pain

Donate to Keep Electric Literature Free!

Electric Literature published over 500 and writers and nearly 600 articles in 2023—all of which are free for you to read. EL’s archives of thousands of essays, stories, poems, and reading lists are also free. We need you to contribute to keep it that way. Please make a donation to our year end campaign today.

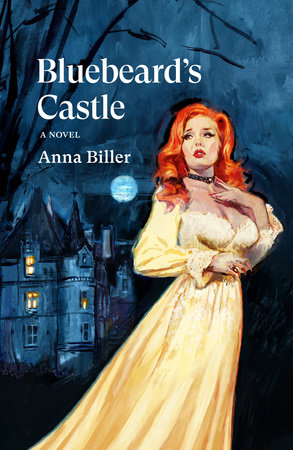

“There are rules for contemporary literature, and I’m breaking a lot of them for a lot of people,” filmmaker Anna Biller told me by phone. Her debut novel, Bluebeard’s Castle, rejects the minimalism that recent fiction sometimes conflates with seriousness: nowhere, here, will you find the anesthetized protagonist, the dead-end job, the lukewarm relationships, or the “cool first person” tone used of late to capture the alienation of the modern subject. Instead, Biller’s book embraces excess from cover to literal cover. Its heroine Judith’s feelings are almost as enormous as the gowns she wears to breakfast and the English castle she buys on a whim with her hunky but probably evil lover. Costume balls are thrown. Daggers are wielded. And just look at that cover!

In reviving the delicious manias of 18th-century Gothic novels and 1960s dime-store romances, Bluebeard’s Castle pays homage to genres that were often (and often pejoratively) associated with female readerships in their day. Indeed, the pleasures and perils of womanhood have always been the twin obsessions of Biller’s oeuvre. As a filmmaker, she painstakingly recreates the dreamy costumes, sets, and cinematography of bygone eras, from ‘60s Hollywood (The Love Witch) to the sexploitation movies and mags of the ‘70s (Viva). The result is a gorgeous, distinctly female gaze—but one unafraid to depict the mainstays of women’s suffering, from objectification to assault.

Even against that backdrop, Bluebeard’s Castle is Biller’s darkest work to date. Her reimagination of the French fairytale follows modern-day mystery author Judith as she falls hard for Gavin, a member of the peerage who promises her the world. But once they marry, Gavin’s charms sour, his worsening acts of cruelty seeming to channel the femicidal history of the medieval estate they call home. As Judith begins to fear for her sanity—and her life—Bluebeard’s Castle indicts a society that dares to call itself modern while violence against women remains routine.

Chelsea Davis: The Bluebeard legend is hundreds of years old. I was curious what attracted you to using it as the blueprint for a novel set in the present.

Anna Biller: It was actually a tragedy that happened to somebody that I know who got involved with a very, very bad man. And her life ended.

I was thinking about all the research on how many women are killed by their partners today—it’s such a high number. There was a story last year about a couple that went hiking. The woman went missing and they did this big search for her. When they combed the woods for her body, they found four more bodies that they weren’t even looking for. Their killers were all their boyfriends and husbands.

Growing up, I was always really interested in fairytales, and in the connection between the Bluebeard fairytale and the modern serial killer thriller. The Bluebeard stories were originally from the point of view of the woman, and it was only maybe in the ‘60s that it shifted, especially in movies. Suddenly, the point of view is all from that of the killer—especially in the Giallo films, like those of Mario Bava, and then in Hollywood films. It became very, very sadistic, and that’s still what we have: it’s the slasher, or the thriller. They say these movies are feminist, because there’s one woman who survived at the end, but in those older movies, you didn’t have to see a bunch of your friends be brutally murdered. I don’t think that’s a happy ending.

So that’s all in the book.

CD: What you’re saying is that femicide is still the status quo, not the exception. We’d like to think of extreme violence against women as being a thing of the past, but it’s not.

AB: That’s partly why I wanted to set my book in the modern age: I don’t want people to think “Oh, this is how it was in the 1950s or the ‘40s.” That lets us off the hook.

People also think of feminine women as dated, of femininity as being out of fashion. But I see more and more young women who really want to doll themselves up. They’re not doing it for a man; usually they’re doing it for fun with their friends, or to make themselves feel good. It’s in pop culture, it’s in music video culture, it’s on TikTok, but it’s still not in recent movies or books.

CD: I wanted to ask you about feminine fantasy more broadly. You’re so committed to a traditionally feminine aesthetic in your films, and now also in this novel: the lavish clothing, the sweet food, the hunky man. And each of these pleasures is actually really fun to read about. But they also end up having a dark side—the sugar crash after the desserts, or the man who ends up being, you know, completely evil. Do you think that women’s fantasy is doomed to endanger us?

AB: No, I don’t think it’s always doomed to endanger us. But do I think the Gothic is about women being entombed within a castle that’s owned by a man, under his rules and regulations. So, the Gothic is about being imprisoned within patriarchy, and about the woman either making peace with that, or escaping it.

That’s why those old-style novel covers are so evocative—the kind of cover that I copied with my book jacket, which shows the woman fleeing from the castle. It already tells the whole story, that cover: she’s fleeing from this wealth, this security, this pleasure, this dark fantasy that’s exciting. The man means pleasure, but he also means control. Are you willing to play the role of the little perfect doll to a man, and have all the money, have all the pleasure—but also be under his control? Or do you want independence, which could also mean poverty and loneliness?

Jane Eyre is a perfect example of that. Jane can go back to the castle in the end and be with Rochester because he’s maimed and blind, and therefore, they’re equal. He doesn’t have power over her because he has to depend on her to be his eyes. But if he weren’t maimed and blind, well, she couldn’t stay there with him because he’d continue to dominate her.

CD: Like he does to Bertha.

The Gothic is about being imprisoned within patriarchy, and about the woman either making peace with that, or escaping it.

AB: Exactly. And that’s why Wide Sargasso Sea was so breathtaking for me. What that novel does is also what I was interested in doing: talking about the wife before the last wife. In the original Bluebeard fairy tale, the main character does survive. But what about the other wives, the wives that were forgotten?

CD: You have a line like that in Bluebeard’s Castle: “[Judith] always thought about characters you weren’t supposed to think about: the girls and women who are murdered in slasher films, rather than the final girl.”

AB: I like to do this obnoxious thing where I directly put my theories and ideas in the text. I know that irritates people, but that’s one reason I made Judith a writer. So she could be someone who thinks analytically like I do.

That’s also part of why Bluebeard’s Castle has so much intertextuality, so many references to other Gothic novels and films. When I’m writing screenplays, too, I’m always thinking, “What does this have to do with other works?”

CD: Do you think that having written a novel now will change how you approach writing screenplays and directing?

AB: Bluebeard’s Castle started as a screenplay. I was trying to get it made as a movie, but couldn’t get it made before the pandemic. So now the movie, if it gets made, is going to really feel like it was adapted from a novel. And if I have time, I would love to actually write a little novella of the screenplay that I’m going to make into a movie now [The Face of Horror], which is in pre-production. Charlie Chaplin wrote novels for his later movies, like Limelight. I think it’s a really good practice, because it gets you to know your characters better. And then it’s more like a memory that you lived, and you can just take the best fragments of it for the movie.

For instance, dialogue always has to be really short when you write a screenplay, because the audience gets bored and they don’t like long scenes. But with a novel, the actors can read the novel and know the rest of the dialogue because they read the book. And that informs the performance.

The screenplay didn’t have a ghost either.

CD: Why did you decide to add a ghost to the novel?

In the original Bluebeard fairy tale, the main character does survive. But what about the other wives, the wives that were forgotten?

AB: I was trying to make the novel as Gothic as possible, and I was reading a hilarious article in the Guardian about what makes books Gothic. There was this whole checklist: you have to have a decrepit castle in the middle of nowhere, and this is how the villain has to be, and there has to be a ghost or monster.

CD: I do think the Gothic lends itself to the checklist approach in a way that not every genre does.

AB: Oh, definitely. The very first Gothic novel, Castle of Otranto, was already a pastiche of medieval romances, very tongue-in-cheek. And with a pastiche genre, it’s like, “Okay, I’m going to take these elements from this genre, elements from the past that already seem really quaint and outdated, and then redo them for a new audience and just have a lot of fun.”

CD: The Gothic is often about working through our relationship with the past, that backwards glance.

AB: Yes, like, “Ooh, look at how things were a couple hundred years ago—it’s so spooky because it’s the past; the castles were darker, and people were more cruel.” Now, we don’t really have the Gothic anymore as a genre; instead, we have horror and we have romance.

CD: And the Gothic, because of its melodrama, did give us access to something that the “literary fiction” as a genre or prestige category doesn’t always, which is heightened emotion, and taboo subjects.

AB: Yeah, well, maybe they’re actually closer to the fairytale and the folktale in that sense, right? Because the fairytale and folktale are all about repeating these motifs that have become like memes in the culture. Things like the Bluebeard story were invented way before [Charles] Perrault—they were old wives’ tales, they were told by the fire, and then Grimm and Perrault just wrote them down. So I think that the Gothic’s a little bit like that—this group of cliches and stereotypes that can be new each time it’s told by a different person. I work that way in my films too: I’m always trying to reference other movies and other eras of filmmaking. It’s like telling a story that’s also about all the other times it’s been told.

I read a really fascinating book called Why Fairytales Stick by Jack Zipes, and it was about how certain stories get retold over hundreds or thousands of years because they’ve got something in them that is important for people to remember or understand.

CD: Some of the social dynamics that were happening then, hundreds of years ago, are still happening now, to some extent. Children are still in danger. Women are still in danger.

AB: People are still dealing with death and neglect and abuse and rape.

CD: Does your book have a pedagogical goal, in that sense?

I hope that my book shows people how to have empathy for somebody in [an abusive] situation.

AB: A few years ago, when a woman was raped, everybody said it was her fault. And now we don’t think that anymore. We’ve actually changed our consciousness as a culture to realize she wasn’t “asking for it.” But we still have the same attitude towards victims of domestic violence: “She was asking for it. If she was smarter, she would have gotten out.” We think that there’s something incredibly wrong with them that they would have stayed with someone abusive. So, I hope that my book shows people how to have empathy for somebody in that situation.

But also, in terms of victims themselves, two women have already told me that they left their abusive partners after reading my book. One woman had been with her husband for fifteen years, and the other had been with her partner for five years. They both told me the same thing: “I realized I wasn’t safe.”

One of the women had a child and two cats that she’s very protective of. And she said that what made her realize she had to leave was that she wasn’t just putting herself in danger, she was putting her cats and her child in danger.

CD: Right, there’s specifically a part in the novel where Gavin becomes a threat to Judith’s cat, Romeo.

AB: You keep excusing [an abusive partner]; you keep taking him back. And I guess these two readers saw themselves in Judith, and they realized, “Okay, I’m doing this, too, and that’s not what I want to be doing anymore.” You also realize that a man like that isn’t going to change, that he’s never going to be how you want him to be.

And I think when the book switches into Gavin’s point of view is when it gets really, really scary. That’s the one part of the book that doesn’t read like a Bronte or like a Gothic—it reads like a contemporary thriller. I did that on purpose, made the language much more direct and plain and contemporary. It’s not the highly feminine writing style of the rest of the book; it’s authoritative, it’s the mainstream style that we accept as normal and fine. But that’s also the really appalling chapter, right? So I wanted to contrast that chapter with the rest of this book so that it seems as obscene as it is.

CD: I thought it was interesting that in the novel-within-a-novel that Judith is writing about Bluebeard, her protagonist gets a different ending from the one that Judith does.

AB: When I was finishing Judith’s story, I found it too bleak. I didn’t want to end it with her tragedy, but instead with her triumph. It was too unrealistic and clichéd, in my view, to give Judith herself a happy ending, considering all that comes before, so I gave the happy ending to her heroine. It’s the ending I wanted, and the ending the reader wants. It also frames the book within a fairy tale, shows us that Judith was well aware of the situation she was in, and it immortalizes Judith by ending with her writing.