Alexandra Chang Turns the Pain of a Friendship Breakup Into a Short Story

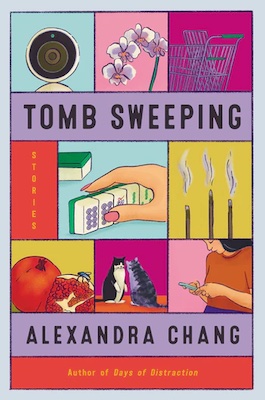

“The world here beats faster than a hummingbird’s wings,” writes Alexandra Chang in her new collection Tomb Sweeping. Chang, the author of Days of Distraction and a National Book Foundation 5 Under 35 recipient, writes poignantly about tenuous connection.

In these stories, a wealthy housewife runs a gambling ring in Zheijiang, a young woman attends the living funeral of a family friend, someone “drinks himself into a dedicated madness,” two friends become further alienated despite attempts to reunite, a brother disappears during Japanese occupation and the Sook Ching. Chang is curious about “the power of angry women” among “men of manageable dreams.” Fathers, fumbling, try especially hard to overcome their blindness; women, taught to behave, speak up and act up, or quit. People create new, impossible lives for themselves despite the risks and resistance, and the oppressive sociopolitical forces against them. There are incidents of misidentification, mistaken identity, doubling, doppelgängers, past selves. Couples uncouple themselves even when they remain together. Work arises as a torture of moral incongruity. Technology is rarely to be trusted. People, bound to one another through obligation, are so mystified by those they’re closest to, they often mislead or fail each other. It is unbearable for many of Chang’s characters to be alone—too often, existential dread overtakes them. The anxiety reverberates through the generations. Yet, undeniably, Chang’s characters harness power from feelings of disquiet. They travel the distance between obedience and the imagination to live a life of one’s choosing despite the weight of history, family, law, and prior selves. In the collection’s first story, aptly titled, “Unknown by Unknown,” a young woman, despite her very real fears, confides that she is “disoriented… in a way that makes me happy to be alive.” We feel that as a great truth of Tomb Sweeping, and of our own lives.

Annie Liontas: Are the characters in Tomb Sweeping lost or wandering souls? What allows them to find themselves or their place in the world?

AC: I do think of a lot of them as lost or in transition or going through some sort of growing pains. Some do find their place in the world, or at least find a sense of peace from that turmoil of feeling lost. For example, Adrienne, the protagonist in “Farewell Hank.” She’s definitely in a long transition: she’s young, she’s cynical, she doesn’t really have much of a connection to people around her. She hasn’t grappled with a central grief in her life. The events of the story allow her to at least face that grief a little bit more, and to find a sense of connection, at least with her mother. That connection gives her, I think, a little bit more stability than she had in the beginning of the story. Other characters are very lost. In the first story, “Unknown by Unknown,” the main character gets laid off from her job. She really has no sense of what she’s supposed to be doing, and then she gets this house sitting gig. That doesn’t give her any sort of long-term stability or a sense of having found a place in the world, but it’s an alluring temporary space where she can imagine herself into another life. But even that gets pretty quickly taken away from her and she’s back in a place of confusion—not the exact same place of confusion, though. And in that story, too, there’s a moment of fleeting connection between her and another character that grounds her.

I’m interested in writing characters who are going through it in some way, and don’t necessarily experience transformation where they transcend into a better being. They move through one phase into another, from transition to transition. If anything, connection with others helps them find themselves and their place in the world, but most of these connections are temporary, too. That’s how I see the world and experience life myself. I don’t think growing pains really ever stop. Transition seems constant, ideal even.

AL: Characters such as the narrator in “Klara” and the father in “Flies” can’t quite get out of their own way. They suffer, as do those closest to them. How would they define happiness? How far out of reach is it?

I wanted to combine the most painful friend breakup I’ve had… and condense them into the story.

AC: The narrator in “Klara” is so consumed by the loss of this friendship that she can’t really think beyond that pain. She’s experiencing it even though that friendship is long gone. Klara isn’t in the narrator’s actual day-to-day life anymore, but she takes up so much space in the narrator’s head because of how important she’d once been to the narrator. She’s in her own way because she can’t let go of this past. That’s true of a lot of my characters. But I do think at the end, she gets a glimpse outside of her pain. She wonders, what would Klara think of me right now? And that’s a tiny step into someone else’s perspective and outside of her own, and she’s able to let go a little bit. Is happiness within reach for her? Happiness for her in that story would likely be a return to their past friendship, which she knows is an impossibility. That’s not to say she’ll never be happy, but what she truly wants is definitely out of reach. Friendship breakups are so hard! It sometimes takes years to get over or let go of the pain of having lost someone who you knew and knew you so intimately.

AL: So that feels very close to your experience?

AC: Yes. In “Klara,” I wanted to combine the most painful friend breakup/friendship loss feelings I’ve had over many years and condense them into the story. I’ve woken up in the middle of the night thinking about conversations that I’ve had with friends who I haven’t been as close with anymore and been overwhelmed with sadness and anxiety, like, what happened? Why were we like this? What could I have done differently? What could they have done differently? That kind of obsessive, often nonproductive thinking is in reaction to grief.

AL: I think about the loss of a friendship as being an open wound, because culturally, we don’t have the language or the framework to define it.

AC: It’s not as simple as those romantic relationship breakups where it’s like, OK, we’re going to talk about it and now we’re over. Obviously it’s not always that clean cut with romantic relationships either, but with a friendship breakup, there really are no guidelines. In “Klara,” these two kind of fizzle apart and there’s no sense of closure for the narrator, which is why, as you say, it feels like an open wound. It’s very hard for her to understand what happened between them, and the narrative of their friendship is always shifting in her head. I’ve been there.

AL: You define culture in these stories as the accumulation of small ubiquitous gestures over time. What are the forces shaping these characters’ lives, whether they realize it or not? What happens when they do realize it?

Sometimes you just really do need to just be in this profound sadness instead of resisting it.

AC: The biggest forces affecting my character’s lives are those that tend to be outside of their control—societal forces like capitalism, class, racism, sexism, xenophobia. A lot of my characters are immigrants or children of immigrants. And a couple stories are set in China, one is set in Singapore. These characters are facing historical forces, the impacts of war, or of governmental policy. And oftentimes they don’t realize that’s what’s making their life difficult, or they’re not always thinking about why it is that they’re running into problems or challenges. They’re often just trying to survive their day to day. A few of them do realize. Like in “To Get Riches Glorious,” I’d say FuFu at some point does understand why she is having such a hard time achieving what she wants in life. She primarily blames it on sexism and the inability for her, as a woman in China, to actually fulfill her ambitions, ambitions that seem more readily available to the men around her. FuFu also comes from a poorer village background, and like a lot of the characters in this book, much of her struggles have to do with the desires for upward mobility. FuFu then has to find a route that’s outside of social norms to get what she wants. And what she does unfortunately lands her in prison.

AL: FuFu is one of my favorite characters! Despite the consequences, she is proud of her independence and the money she made through illegal gambling, and seems to have no regrets. Patricia, in “Persona Development,” likewise turns away from a life of security, in preference for one more aligned with her true self. How do you understand these women’s choices and brazenness?

AC: FuFu and Patricia are such different people, they’re almost on the opposite ends of the spectrum in terms of what they want. But both of them have to have the courage to go for something they want, even though they struggle along the way. FuFu became more clear to me as I lived in that story. I knew that I wanted to write a woman who would end up in prison. I had been reading this dissertation about Chinese women in prison, and I wondered, what leads up to this moment? The more I wrote her, line by line, she became this very confident and very defiant character. In a way, she develops these traits because of the very constraints and expectations placed on her. A lot of her choices are about pushing against the constraints, and I think FuFu makes a great effort to throw off what’s placed upon her. She’s compelling to me, too, because she’s not a character who I relate to closely. I wouldn’t be capable of going the lengths that she does to get what she wants. In many ways, I admire her abilities and her sense of self, even if they are misguided at times. She really doesn’t backtrack on her decisions. That story also zooms out and shows many women who are going against societal norms.

Patricia’s defiance in “Persona Development” is more personal. It’s also culturally based, just in a very different world. She’s this successful Director of Marketing at an agency in the States who has embraced these working-woman vibes, girl bossing her way up, but finds herself unsatisfied. So her defiance is more about turning away from that world and trying to figure out what she truly wants.

AL: In “Tomb Sweeping,” a medium meets an unexpected and chilling end, one which haunts the narrator. What questions is this story asking about guilt, inheritance, and the past?

AC: That story is about trying to understand what we owe one another in the aftermath of mistakes and intentional harms that have been committed in the past. The story is told through the perspective of a twelve-year-old girl who’s grandfather lived through the Japanese occupation of Singapore during World War II. Her grandfather’s brother was murdered by Japanese soldiers, and her grandfather is very adamant about her understanding this history. But he does so from a very wounded place and is holding onto a lot of hatred. This comes to a head when they encounter a medium who is half Chinese and half Japanese. The medium represents something very upsetting and disturbing for the grandfather. But this young girl, who has not lived through that pain and who only knows it secondhand through her family, is trying to grapple with what she inherits from this past. What do I do with this legacy? How do I navigate it? Who is at fault and who carries the guilt for what has happened in the past? How can people today right these wrongs? She doesn’t necessarily come to any answers, and neither does the story. I don’t really feel like I have answers either. That’s what draws me to stories, having questions that I don’t have answers to and still don’t have answers to after writing them. It’s more about trying to wade into the questions and see if anything can be uncovered—not an answer so much as a feeling for how to live.

AL: You wrote this collection before the novel, but decided to keep working on the stories. What went into that decision?

AC: Cumulatively, I’ve been working on these stories for nine years and I sold them at the same time as the novel. If the collection had been on schedule, it would have been published a year or so earlier. But at that time in my life, when I should have been working on the stories in order to meet my deadlines, it was deep pandemic and I had just moved to a new city. The state of the world was terrible, I was consumed by the news, consumed by what was happening around me. And then, on a personal level, I was feeling very helpless and distant from loved ones. I was, to be honest, very depressed. I just did not see the importance of these stories. I understood on a logical level that this book was under contract and that it wasn’t a huge deal whether I finished them or not, so why not finish them? But on an emotional level, I just wasn’t in a place where I could do it. I didn’t feel a connection to the stories or to writing fiction at all. I thought, Maybe I’ll never write again. It was pretty devastating. I don’t think I wrote anything for over a year. Sometimes you just really do need to just be in this profound sadness instead of resisting it. I guess that was the way that I was able to come out of it.

Over time, the stories began to feel new to me again, and I became a little bit more interested in what they were doing, maybe because the stakes felt lower. I told myself, I don’t have to be a writer, I can actually walk off that path. It’s not life or death for me, I can step away from it. Teaching helped with continuing with the stories, too. Going into a classroom where there are young people who are like, “I love books and I love reading!” I was reminded, “Oh yeah, me too. I do love that!” Eventually I got to the point where I thought, I can do this. I want to return to these stories renewed.

AL: Most of these stories resist neat or definitive endings. How is resistance to closure true for you?

AC: I just don’t believe that there are super clear-cut answers in life, or very clear-cut ways to live. Maybe one day I’ll turn a certain age and think, actually, this is the way to live, but I haven’t experienced that yet. A lot of my characters, like me, struggle with what is morally right and wrong in certain situations. They often land in ambivalence, that things are not so black and white. What might seem right thing to do could cause harm… There is nuance in every situation. There are times when I worry I lean a little too much into nuance or into this gray area. Obviously, there are times in life when I feel very strongly about something being evil and clearly harmful in the world. But that’s not really what I’m interested in exploring in fiction. When I’m writing, I want to feel like I could discover something new. I don’t want to have an answer already in my head and then write towards the answer. That’s boring for me as a writer. These stories don’t have neat, tidy endings because I want to leave the door open for possibility.