Annie Liontas on “Sex With a Brain Injuryâ€

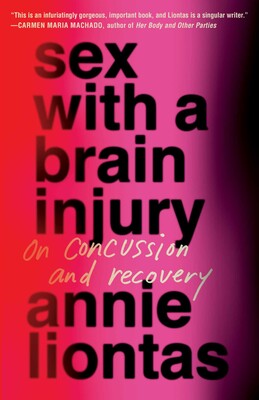

The new memoir in essays Sex With a Brain Injury from Annie Liontas, author of the novel Let Me Explain You, is a highly formally and thematically risky work of nonfiction exploring traumatic brain injury (TBI), queerness, addiction, mass incarceration, and chronic illness. Weaving “history, philosophy, and personal accounts to interrogate and expand representations of mental health, ability, and disability—particularly in relation to women and the LGBT community,” Liontas accomplishes a stunning feat of imagination, empathy, play, witness and reportage.

Though named after Liontas’ widely praised essay of the same name, the memoir never falls into the easy groove of being a book centered around a single successful idea, and resists plot summary. Using interviews with their wife, an innovative collaboration with a previously incarcerated writer, research, reportage, erasure/redaction, and song lyrics, it’s the kind of book that, when one is done, you turn over in your hands asking, how did they do that?

Though Liontas and I are friends and neighbors in West Philadelphia, we crafted this interview together in a digital format, which allowed for a pleasant and plaintive evolution of ideas, for me to respond to Liontas’ periodic parenthetical apologies—“brain a little slow”—with explanation points and my own updates that I, in a place of grief after just losing my father, was inspired to listen—playing it loud in my office as we typed back and forth to each other—to the absolute banger that is Bruce Springsteen’s “Dancing in the Dark.”

Emma Copley Eisenberg: Annie, you are a novelist and now you are an essayist too. What is an essay to you?

Annie Liontas: I’m thinking about Alexander Chee’s quote, “A story is something you want to run away with, an essay is something you can’t run away from.” I love your question, because we don’t really know what an essay is—is it an argument, is it about perspective, is it about making meaning through reflection—but Chee’s assertion really gets at something for me. I wasn’t consciously building a collection or memoir-in-essays when I first started, but I pretty quickly realized that this work had to be nonfiction. All of the stories we have of head injury are fiction (even when they’re not), because we don’t have the cultural framework to talk about them the way we do addiction or smoking.

We’ve known since the Egyptians and Greeks what head injury does to the body and person, but we forget what we’ve learned, or we suppress the knowledge through powerful entities like the NFL—and that means the culture hasn’t yet had the chance to masticate and process the knowledge, or change public policy. I felt that I needed to keep asking these questions, and turning the thing on all of its faces to do it any justice. I also hold onto what Annie Dillard says about how an essay is a moral exercise that involves engagement in the unknown, that it can be about civilization but at the end of the day, what matters in this is you.

ECE: I am always telling my students the formal choices you make in an essay will inevitably be connected to what the essay is about. I also went to a talk where Rebecca Makkai said that in every project she’s done, she’s never solved a major problem by writing around it, only by bringing it to the center. How did you think about the problem of writing about head injury/TBI in the ways it “makes things fiction” or destabilizes things?

All of the stories we have of head injury are fiction (even when they’re not), because we don’t have the cultural framework to talk about them.

AL: I would have done the book—and, by extension, the millions of “walking wounded,” as survivors of TBI are called—a great disservice if I had not confronted the bodily experience of injury. The condition is really one of erasure, because it’s not a visible condition, and therefore often dismissed or disbelieved by our highest medical and legal institutions. Paul Lisicky calls it getting blood onto the page, and each time I sat down to a new chapter, I asked myself: what is happening to a body in pain? How can I more precisely capture the physical? How can I, even when I’m writing about anger and Henry VIII or Abraham Lincoln and depression or Lady Gaga, or whatever, honor what people are going through and have been going through invisibly, and sometimes for years. So I think it was mostly a gut check about being honest, and direct, and grounding the abstract and the intellectual in the felt experience.

ECE: That makes a deep kind of sense that you were trying (and succeeding) to render the bodily and physical experience because there is something absent or erased at the very core of what you’re trying to say. That does make me think of the erasure essays—there’s three I believe—in which you interview your wife, as well as some of the other craft risks you take in the book—post it chapters, super short chapters, a co-written essay, research and reporting. Were these craft choices a part of your vision or responses to problems/impasses you hit with more traditional forms of narrative? Were there other craft things you tried that you ultimately discarded?

AL: Those erasure essays were a huge risk! I had to be like: “Babe, can I interview you about the worst period of our lives and then let strangers read it?” Lol. In actuality, S and I had a series of recorded conversations, and then I gave her the transcript and a sharpie and said, cross out what you don’t want published. It was an opportunity to extend conversations we were having in our private life and marriage, but also a way to honor and recognize that, while the multiple concussions was an experience I was isolated inside of, I wasn’t the only one being impacted. She was—is—too. I thought of all the partners and family members and best friends out there similarly suffering silently, and knew that I had to get outside of my own voice and experience. And traditional form didn’t allow for that. I had to invite other voices in. So, yes, while it wasn’t my initial vision, these craft choices are seeking to offer dynamic responses to a set of fairly unanswerable questions. As you note, I do have a collaborative essay in here, one that started as a profile, and I include other testimonies as well–people I’ve met with head injuries, for instance. The work had to expand to ensure they were all heard.

ECE: I loved “Professor X,” the collaborative essay about head injury and legal reform and the implications head injuries have as predictors for future incarceration. You said this began as a profile, can you tell us more about how this essay came to be and what it was like to write collaboratively?

The condition is really one of erasure, because it’s not a visible condition, and therefore often dismissed or disbelieved by our medical and legal institutions.

AL: Thanks for asking—this piece is perhaps the most important to me because of the stakes and what it’s trying to do, and the impact it seeks to make in the world. When I was researching discrepancies in the criminal justice system and our treatment of incarcerated people with TBI, I was stunned to learn that people who are in prison are seven times more likely to get a head injury before they ever step inside a cell. You imagine that number will be high, but seven times? It’s a reminder that we incarcerate sickness, as my co-author Marchell Taylor often says. I reached out to Dr. Kim Gorgens, who is doing incredible research about TBI and the prison system—her current staggering data suggests that 97% of repeat female offenders had a head injury in the last year—and Kim connected me to Marchell, a Denver businessman and former inmate-turned-advocate. I thought I was going to write this very distanced, researched profile on Marchell, but we very quickly got close. We became friends, and the process became far more organic than simple interview. We spent hours on Zoom, during which he shared his story through oration, and then I’d work the thing into written text, and we’d go back and forth. It took many months, lots of chats and texts, and eventually some kind of barrier between us fell and we were seeing each other in our suffering. Marchell’s gift is empathy, and connecting with people, and so even though I really wanted this to be about him, he pushed me to engage more deeply, and we decided this had to be a collaboration.

ECE: That’s so beautiful and speaks to your skill as an interviewer, a curious person excited to look outwards and render what’s going on in the wider landscape of TBI as well as look inward and interrogate what’s going on in on the level of the interior, the personal. One of the essays that especially stayed with me was “Dancing in the Dark,” about your mother and her queerness and her addiction. On the surface this one isn’t as explicitly connected to the theme of TBI and invisible injury, how do you see this one fitting within the broader things you care about in this book?

AL: “Dancing in the Dark,” at its heart, is about me grappling after forty years with my mother’s addiction and queerness. She was an immigrant who was conscripted into an arranged marriage, and while I always had sympathy for her, I think I reacted the way that many children of addicts do, which is to resist the experience and even the narrative—to say, That’s not me. What I understood—as a queer person dealing with a chronic condition and post-concussive syndrome—was how invisible her suffering had been. I had to reckon with that, and admit my own culpability in being willfully blind. Then I learned that scientists are discovering addiction and head trauma look similar in the brain. That is, damage is damage. I was floored by this. Suddenly, my mother’s experience and my own were not very far apart, and I had to ask myself what it must have been like for her to suffer unseen.

ECE: You write, “Never marry a writer, they live two truths at once, both the story they tell and its revision.” There’s a lot in this book about lies, doubt, duplicity, and storytelling. I was lucky enough to be on a panel with you last year at AWP called “Hide and Seek.” There is a sense of duplicity and hiding and seeking in this book in the best way. Why was it so important to you to write explicitly about lies and doubt?

Art, even when you’re broken, can make you feel whole.

AL: A couple of the pieces interrogate the relationship between our public and private selves, and how we must navigate those selves in a capitalist country that demands our full and complete participation: that is, we must at all times create an illusion of wellness and vigor, even when we aren’t well, even when it’s impossible to get out of bed. I had been taught those values, too, as an immigrant from Greece. My father was a welder, my parents were illiterate grape farmers, and no matter what was going on at home—the family, the body—you had to get up and work and produce. I think this was also the kind of erasure I was resisting with essays like “Doubt, My Love,” the fiction of the perceived self that is in service of others even when it comes at great cost. We occupy those false selves even in our most intimate relationships—marriage, for instance—because the borders bleed, and after years of training it can become almost impossible to locate the authentic self. Then one day you wake up and think, Why doesn’t anybody see me?

Most people going through TBI, especially women and people of color, are not believed. Outside of the NFL and sports, we have a very limited lexicon and almost no mental image of what “concussion” means. For instance, girls who play soccer are twice as likely as boys to get head injuries, yet we rarely discuss that. The female body is more vulnerable to concussion, and to post-concussive disorder, but we don’t talk about that, either. Instead, the medical profession and culture seem to trace this back to hysteria, calling it psychosomatic, and dismissing peoples’ actual experiences.

ECE: There’s also a great deal about other kinds of art and creativity other than writing in this collection. We get Bruce Springsteen, we get dancing (a lot of dancing!!), we get your wife the architect, we get riding a bike and a list of song titles. Is there a way in which this book is about art as an enterprise or about how brain injury impacts being a maker and receiver of good art?

AL: Yes a lot of dancing! Where I’m from, we call it “Church”! I’m drawn to all kinds of art, as I think most artists are, so even if this weren’t about brain injury, it would have been hard to keep art out of these pages, and how it gives us our humanity. But perhaps the inclusion of the Springsteen lyrics and these other artifacts serves as a tool to further capture the experience of injury and dislocation. On my worst days, I couldn’t listen to music, or exercise, or watch TV, or read. But on the ok days, even when I knew tomorrow was probably going to suck, I could listen to “Dancing in the Dark” and take a walk and feel like some part of me was still alive. Art, even when you’re broken, can make you feel whole.