It’s time to figure out global space traffic management

The recent acquisition of geospatial intelligence firm Orbital Insight, which has a satellite imagery search engine platform, by Privateer, the Steve Wozniak startup that came out of stealth to raise $56 million in Series A funding, may have important consequences for how we manage space traffic.. It stresses end-to-end vertical integration, cross-functionality, and newfound alignment between the Earth observation segment thanks to the two companies’ focus on imagery and analytics aggregation, space traffic management and situational awareness.

As originally reported by Reuters, this will see Orbital’s TerraScope Earth observation platform — a search engine of aggregated satellite imagery — combined with Privateer’s satellite-tracking software.

This acquisition can be seen as a case of diversification and streamlining business opportunities. But can it, even inadvertently, create greater awareness of the need for a normative order for space traffic management? Establishing one would be a prerequisite for laying down liability clauses for issues regarding orbital debris, and making it possible for companies to operate in space in a more thoughtful manner.

Space Wild West?

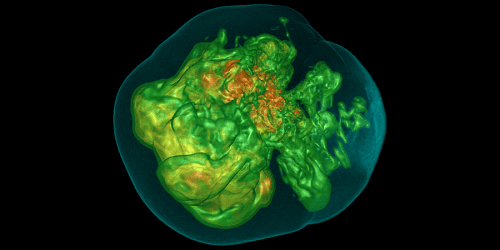

Privateer Space’s name conjures the autonomous spirit of footloose and intrepid navigators. The company tracks satellites and orbital space debris in real time, providing a view of satellites in orbit on its Wayfarer app. This information is crucial for collision avoidance and orbital maneuvering.

The exponential increase in satellite launches, and the modern world’s reliance on the eyes in the sky for everything from disaster management and supply chain monitoring to defense create another mounting problem: space debris.

This junk — estimates say there are more than 50,000 flying objects — pollutes the space environment and creates a high risk for other satellites. A collision would disrupt their functioning and place them out of orbit.

While there are laws in place that prohibit space weaponization, such as the 1967 Outer Space Treaty or the recent Artemis Accords that reiterates space as mankind’s common province, pinpointing infractions or laying down accountability is still a no man’s land with many unresolved questions.

Perhaps this is what Alex Fielding refers to when he says there are currently only “stopgap” measures concerning space traffic management.

Leading space environmentalist and Privateer cofounder Moriba Jah told GeoSpatial World in 2022 that a spirit of custodianship and resource stewarding is necessary in order to circumvent a free for all Wild West in space. This can only come with transparency, accountability, trust, and most importantly robust collaboration.

“If we as a world come together to define orbital carrying capacity and identify the objects in an orbital highway, then we can pinpoint the countries responsible for those objects,” he said in the interview. “This would enable us to clearly see who is occupying most of the capacity in the orbital highway.” There are precedents for how this can be accomplished in air traffic management, road safety norms, food safety and environmental protection — which came into being through sustained efforts, multi-stakeholder collaboration, technology evolution, democratized access and recognition of risks and pitfalls.

A new order?

In his 2021 Financial Times Book of the Year “Exponential” Azheem Azhar talks about the widening gulf between innovation and our existing institutions and legal frameworks. In order to break this stalemate and progress towards a participative, inclusive and open model of space, any lead that breaks from the old status quo assumptions is a fresh start.

In our era of multipronged crisis and fragmentation in the world order, establishing the institutional governance of space in a way that’s acceptable to all may sound idealistic. But with the congestion of Low Earth orbit and the dreaded outcome of Kessler Syndrome, sooner or later, a fresh spurt of creative thinking will be needed.

Akin to international maritime laws or the stance against nuclear proliferation, a new normal of space governance will be required. And it must account for changing realities on the ground, enhanced complexity, and the multiplicity of actors over time.

While it still remains to be seen whether the new space era will expand as though we are at the ‘inflection point’ of exploration, as Deloitte Chief Futurist Mike Bechtel calls the moment before industry explosion.

Whichever way this governance heads, sustainability is an imperative. Space companies that deal in optimal launch planning, orbital maneuvering and monitoring may themselves lead to the clamor for regulations akin to emissions monitoring in the automobile industry or methane flare-up accountability for oil firms.

There’s a need to articulate wide-ranging principles that underlie the ethics of collective cosmos, and inculcate a conscientious sense of responsibility, trusteeship and kindred spirit among us shared inhabitants of the same pale blue dot. But a journey cannot start without identifying the roadmap and a shared vision of where we want to end up.

Aditya Chaturvedi is Deputy Editor at Geospatial World. He is a keen observer of the intersection of modern day technology, society, economics, pop culture and geopolitics.

Related

Read the original article here