Prequel Problems: Why Are TV Execs So Fixated on the Past?

“The most important things to remember about backstory are that (a) everyone has a history and (b) most of it isn’t very interesting.” — Stephen King, On Writing

Sequels used to be the way film franchises were created, but these days, prequels are the preferred mode of extending a TV series.

It’s almost as if TV audiences explicitly asked for stories set in the past of their favorite shows at some point.

Whether they were asked or not, TV executives are banking on audiences who want to know how every story ends before it starts.

Related: The Age of Nostalgia: Why Young Audiences Are Seeking Out Old TV

Where did this prequel trend come from, and why has the TV industry embraced it so thoroughly?

Is it solely about money, or is there a more significant cultural reason keeping our collective gaze focused on the rearview?

Prequel vs Sequel

Movie sequels as a concept stretch back to the beginnings of cinema, and movie series (or franchises) are not particularly new either, as seen with the James Bond films that started in the 1960s.

The 1970s brought us into the age of “numbered” sequels, i.e., films that keep the original’s title and add a number, like Jaws 2.

These sequels rarely advanced the story, and they usually just remixed the original in a worse way.

However, sequels maintained a timeline that moved forward, whether they were set just moments after the previous film ended or after a time jump.

Aside from the odd stealth prequel (like Temple of Doom in 1984), the concept of filling in the backstory of an existing film is a relatively recent phenomenon.

The biggest modern influences were the Star Wars prequels, with their galaxy-spanning lore, and the rise of movies based on comic books, where origin stories are hugely important.

These digressions into the past somehow became the norm in the TV series format over the past couple of decades, to the point where most “new” shows now are offshoots of previously existing ones.

The Appeal of Prequels

One downside of traditional sequels is that they keep a franchise tied to the original actors.

This can be an instant audience draw for future installments.

Still, it can also create scheduling and creative difficulties if the original cast isn’t available or actors have aged out of their roles.

Another downside is the need to keep creating installments of a continuing story even after the initial premise or source material has been exhausted.

Prequels, on the other hand, use the beginning of the original story as an ending to work toward.

This provides a great deal of freedom in choosing the timeframe of a prequel and allows the opportunity to use a completely different (younger) cast for an established set of characters.

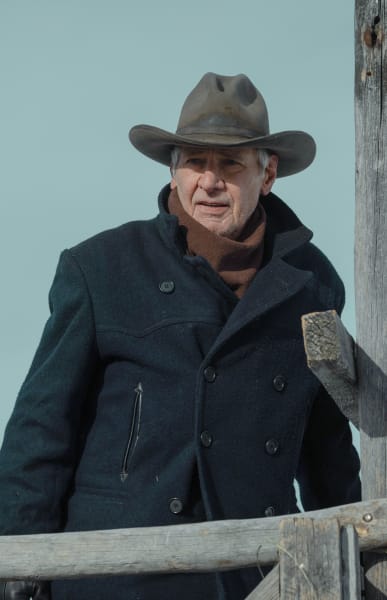

Yellowstone creator Taylor Sheridan used this freedom to great effect by setting the show’s prequels at very specific years in the Dutton family history.

1883 marked the beginning of the Dutton saga, with the journey out West of their original ancestors.

Related: Elsbeth Backlash: Has CBS’ Lighthearted Murder Mystery Lost Its Way Already?

This series also has the distinction of being truly limited to one season, both by Sheridan’s expressed wishes and some pretty hard-to-undo events in the finale.

1923, on the other, hand is returning for a much-needed second season that will bring prodigal son Spencer Dutton back home from overseas to defend his family’s ranch from the army led by strongmen Banner Creighton and Whitfield.

The world of the original story also helps form a retroactive template for any prequel spinoffs.

Knowing a story’s future history combines the satisfaction of puzzle-solving with the comfort of not having to worry about which characters survive because that’s a known quantity.

This is where the widespread popularity of prequels becomes confusing.

Is Spoiler Culture a Factor?

We’ve entered the Golden Age of people who read the last page of a book before buying it.

If The Twilight Zone TV series and M. Night Shyamalan’s films represent one extreme of the surprise twist spectrum, then we are living at the farthest opposite end.

Prequels are not the only indication of this.

There has also been a recent resurgence of Columbo-style detective shows like Elsbeth and Poker Face, in which the audience knows the killer’s identity from the start.

Elsbeth’s Season 1 finale cleverly strayed from this pattern for solid narrative reasons.

If art reflects the societal conditions it’s created under, then uncertain times might indeed explain an outsized desire for predictability.

There is also the real possibility of spoiler fatigue.

With entire seasons of shows dropping all at once, it’s become virtually impossible to avoid headlines announcing huge plot reveals the second you go online.

Surrendering to the inevitability of spoilers might have been the only real choice for those who wanted to continue enjoying TV shows.

However, one could argue that we’d been moving toward our current era of prequel saturation even earlier than that.

After all, if the criterium is knowing how a story ends, then the 1997 film Titanic could technically be considered a prequel, and it did pretty well at the box office.

What Do We Want From Prequels?

It should be easy by now to guess why TV execs love prequels: they offer brand recognition, a guaranteed audience, and unlimited potential for expansion.

Why do *we* keep watching them, though?

Beyond the comforts of connecting the “canon” dots of our favorite IPs, there would seem to come a point where enough of a show’s history has been sifted through to satisfy even the most diehard of fans.

Young Sheldon was a wildly successful prequel partly from residual goodwill for the adult character from The Big Bang Theory but mostly because it was an engaging story setup on its own, as it followed a genius child growing up in a conventional family in Texas.

This was exactly what the prequel genre was made for, where a character’s history deepens and expands our understanding and enjoyment of them and their world.

We all contain multitudes, as do our most beloved TV characters.

However, those characters weren’t always with us.

They were once part of an entirely new fictitious world that we entered without centuries of backstory.

And we fell in love with them just the same.

We might consider leaving room for original stories so we’re not reliant on prequels and don’t have to do weeks of homework viewing to watch and enjoy a TV show.

Culturally, this prequel trend could be an attempt at a version of community, a way to narrow our exponential online choices into a more manageable group of shared stories.

Or, it could just be a natural business response of the entertainment industry to go all in on prequels since they’ve been the most successful form of film and TV projects over the past two decades.

What’s Next?

Prequels have benefited from TV audiences’ taste for binge-viewing.

The urge to click “Next Episode” repeatedly blurs the ends and beginnings of a show’s seasons and softens the narrative passage of time.

Bingeing also lowers any resistance to introducing new characters, actors, and settings since, with prequels, they still inhabit the familiar world of the original show.

Related: Based on a True Story: The Best TV Created from Real-Life Events

It’s not as jarring an experience as starting a completely different series that requires a brief acclimation period.

However, viewers might want to examine the impulse to constantly return to our previous entertainment choices, especially if it’s just to avoid the slight discomfort of the unknown.

Good stories don’t start at the very beginning; they start at a point of change.

Prequels ask the wrong questions of an original show.

They demand linear, cause-and-effect explanations for current character traits and both literal and metaphorical roadmaps for places that were never meant to be named.

Plus, there’s no chance of ruining the pristine memory of an existing original show if you never move beyond it in time; you only play with what events might have happened before.

If we’d only set ourselves free from the dominance of prequels, there are so many new TV shows we could enjoy (such as the hundreds of historical romance novels aside from Bridgerton that could be adapted).

It isn’t easy to imagine a TV landscape like that when there aren’t many new shows to choose from.

But making a point to watch a new show every now and then might help increase the variety of TV content in the future.

Related: The Age of Nostalgia: Why Young Audiences Are Seeking Out Old TV

What do you say, fellow Fanatics — do you have a favorite prequel series?

Let us know in the comments!

Paullette Gaudet is a staff writer for TV Fanatic. You can follow her on X.

Read the original article here