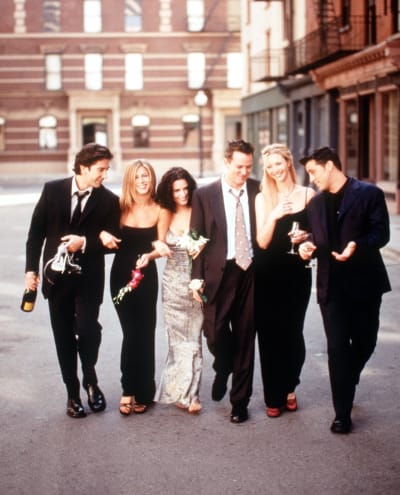

What Generation Was “Friends” Anyway? GenX, Boomers, or Millennials?

Jerry Seinfeld is still haunted by his TV mother’s words — “How could anyone not like him?”

No wonder Seinfeld has been all over social media in recent months.

He forgoes his usual stoicism and criticizes everything in sight, from critics of his movie “Unfrosted” to Howard Stern, college campuses, and even the cast of Friends.

In a recent interview, Lisa Kudrow stated that Seinfeld tried to take credit for Friends’ success and implied that if not for Seinfeld laying the groundwork for a quirky New York group of misfits, the show would never have made it.

To this day, many Seinfeld fans think Friends was a rip-off of Seinfeld that just happened to inherit a cushy Must-See TV time slot.

However, Friends fans, and even some Seinfeld fans, quickly point out that Friends’ humor is nothing like Seinfeld’s outlook.

The issue may be confusing when one tries to break down each show into a generational zeitgeist.

Seinfeld is blatantly a Boomers-era show, created by two of the Boomer generation’s most outspoken and influential minds, Jerry Seinfeld and Larry David, who wrote their show for young-at-heart, 35+ demographics.

Friends was marketed at a younger demographic as if to say this was a New York-based comedy about finding and avoiding love, but it was one aimed at Gen Xers rather than Boomers.

What I remember most about Friends is that it lacks a clear cultural identity. It’s one of the very few shows that feels timeless and utterly oblivious of what generation it’s in.

Friends is decisively not Generation X, as there is hardly any grunge, goth, or counterculture in sight.

There is hardly any discussion of music.

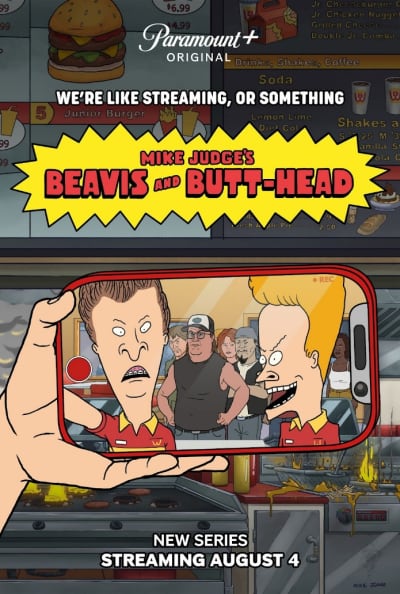

Even shows like Beavis and Butt-Head and Daria understand how music can shape culture and influence some characters’ attitudes and decisions.

Friends seem, at times, oblivious to 1990s culture and even weary of the early 2000s culture when the world was slowly but surely becoming tech-hungry.

What’s amusing about Friends is that it could just as easily take place in the early 1900s, just as much as it could occur in the early 2000s.

Suppose you were to substitute pivotal moments in Friends involving prematurely delivered voicemail messages with hastily written snail mail letters.

In that case, you might have a compelling Elizabethan comedy-drama or a slightly less ridiculous Bridgerton.

One could argue that Friends boldly explored sentimental territory that Seinfeld never did.

It was a show in love with people in love and fascinated with the emotional turmoil of 1990s twentysomethings addressing their neuroses by dating the wrong kind of person.

Even better, they all did find love — er, sorry, Joey — and lived suburbanly ever after by the series finale.

In that respect, the open-hearted, emotionally driven plots make Friends seem almost millennial or zillennial in nature…

Except for the glaring fact that most Gen Yers and Gen Zers don’t get Friends at all and are horrified by the sentimentalization of antisocial behavior!

It’s a show that glorifies its self-centered characters and mocks their barrage of foolish lovers.

Unlike Seinfeld, which was a Vaudevillian parody of romantic comedies (with characters so cartoonishly villainous the writers sent them to jail in the end), Friends seemed to believe in the absolute “Lawful Good” of all its characters.

And that was the part millennials never agreed with.

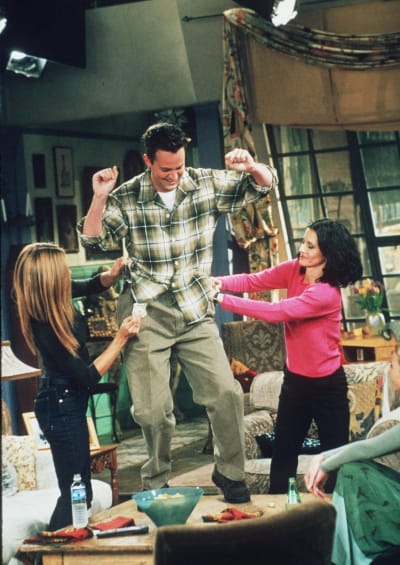

Ross was a cheater, Rachel was shallow and manipulative, Chandler was petty and vengeful, Joey was unethical, Monica was bullying, and Phoebe was, well, socially awkward to the point of psychosis.

Yes, none of these subplots were meant to be taken seriously.

A massage therapist biting a client’s butt, or leaving an ex-girlfriend handcuffed in the office overnight, were exaggerated comedy skits on par with Wiley E. Coyote or at least Al Bundy.

(Let’s not forget Married…With Children preceded cartoonish sitcoms with antiheroes long before Seinfeld did.)

Nothing mattered in the Friends universe so long as it made you laugh.

I got it, even as a Gen Xer who was not too in love with the show’s mawkish writing.

Friends was not a commentary on ethics or morals.

In that respect, Friends benefitted from Gen X’s rampant “nothing sacred” culture in the 1990s.

In doing so, however, it alienated future millennials, who recognized Friends as a non-millennial show writing about stuff that only Boomers and Gen Xers seemed to understand.

It irritated Generation X because the show’s writing was too self-important and open-heart, lovey-dovey to speak to the most disenfranchised generation.

It lacked the edge of other 1990s cultural landmarks like Daria, WWE Monday Night Raw, Beavis and Butt-Head, and Sex and the City.

Friends was a declawed 1990s phenomenon, like a more sex-positive TGIF show, and looked spectacular when compared to the drudgery of Family Matters and Step By Step, which were paranoid of teenagers even discussing sex.

However, the show’s ambiguous culture is not accidental.

In fact, Friends was invented by David Crane and Marta Kauffman, two of the most prolific Boomers of the 1990s.

Previously, both Crane and Kauffman worked on the HBO series Dream On (1990-1996), which was so Boomer-riffic, that it alienated mainstream audiences and only found its niche on HBO.

Despite being the first American sitcom to feature nudity and swear words, Dream On was surprisingly nostalgic and sentimental.

The show even used old black-and-white television series clips to illustrate Tupper’s old-fashioned stream of consciousness.

Of course, it never found anything besides a cult following since Martin Tupper, a divorced New York City book editor, was hardly a youth-friendly icon.

It was clear that Crane and Kauffman had to think younger, even though their Boomer comedic sensibilities were already highly developed.

Now, what if there was a way for these Boomers to transplant their midlife crisis brains into some sexy twenty-something skinsuits?

A twisted form of immortality, not exactly like the movie Get Out, but close enough!

When I first saw Friends in the 1990s, I saw it as yet another New York-centric, Woody Allen-esque romcom, as they were everywhere at the time.

I laughed, sometimes against my will, because despite all the happy feelings, these were genuinely funny people.

Upon repeat viewings twenty years later, the humor still hits its mark, and it’s incredibly cool that a bunch of twenty-year-old actors mastered comic timing so young.

It ages well in that it accurately depicts 20-year-olds as imperfect, occasionally heartless, and, well, kind of dumb — as they should be!

Do we put so much pressure on young adults today that we expect them to make no mistakes and go virtue-signaling without double standards every second of every day?

Isn’t human hypocrisy one of the tenets of timeless humor?

It’s also charming in a nostalgic way that the Friends characters never completely abandoned their souls, as did the much funnier Seinfeld Alumni—whom Larry David insisted were on a smelly car ride to Hell.

These were dumb college kids who tried their best to grow into cautious adults.

However, as I realized the inherent value of Friends’ message, I couldn’t shake the feeling that these characters were not true Gen Xers speaking to us about their world.

These were Boomer writers cosplaying as Gen Xers and discovering a “fountain of youth” by recreating their comedic sensibilities in much younger bodies and culturally oblivious character arcs.

To watch Friends today, or twenty years ago, or one hundred years ago, is merely to watch a timeless story of stunted emotion from post-adolescents who never wanted to finish high school and preferred their silly, shallow romantic lives to the hustle and bustle of career, and finding their true life’s calling.

It’s like listening to a Boomer confessional about how they wish they knew back then what they know now.

Friends is the perfect example of embracing the wonderful things of today that we old people can no longer have, even if it’s just by telling a story about how awesome it would be if you could try it all again.

Michael Arangua is a staff writer for TV Fanatic. You can follow him on X.

Read the original article here